The move from analog to digital technology reveals new global risks for private businesses and individuals

It didn’t take the Russians long into World War II to start spying on their former allies. They’d been setting up listening devices in buildings and meeting locations during the war. But after Germany surrendered everyone assumed the espionage would ratchet up. When U.S. officials conducted a sweep of the American embassy in Moscow in late 1945, agents turned up 120 microphones hidden in the walls, lamps, floors, and furniture.

As the Cold War intensified thirty-five years later in the 1980s, the Reagan White House decided it needed to be craftier than the Soviets at espionage. We knew nearly every American outpost was riddled with bugs as they had been for years and efforts to find and stop the leaks were failing.

In February 1984, President Reagan approved Project Gunman, a six-month NSA effort to remove all electrical equipment from the U.S. embassy in Moscow, transport it to Fort Meade, Maryland, for examination, and replace it with guaranteed bug-free technology.

In the analog era of the Cold War, American and Soviet technology differed dramatically. Like how wall outlets differ from country to country today, the way everything from engines to pens worked differed between the East and West.

At Fort Meade, NSA Deputy Director Walter G. Deeley made it his mission to root out the source of leaks. They knew they were somewhere in the trove of IBM Selectrics typewriters, safes, locks, and more. Deeley also knew the Soviets were further ahead than the Americans in eavesdropping. They had less red tape and, arguably, less scruples about the process.

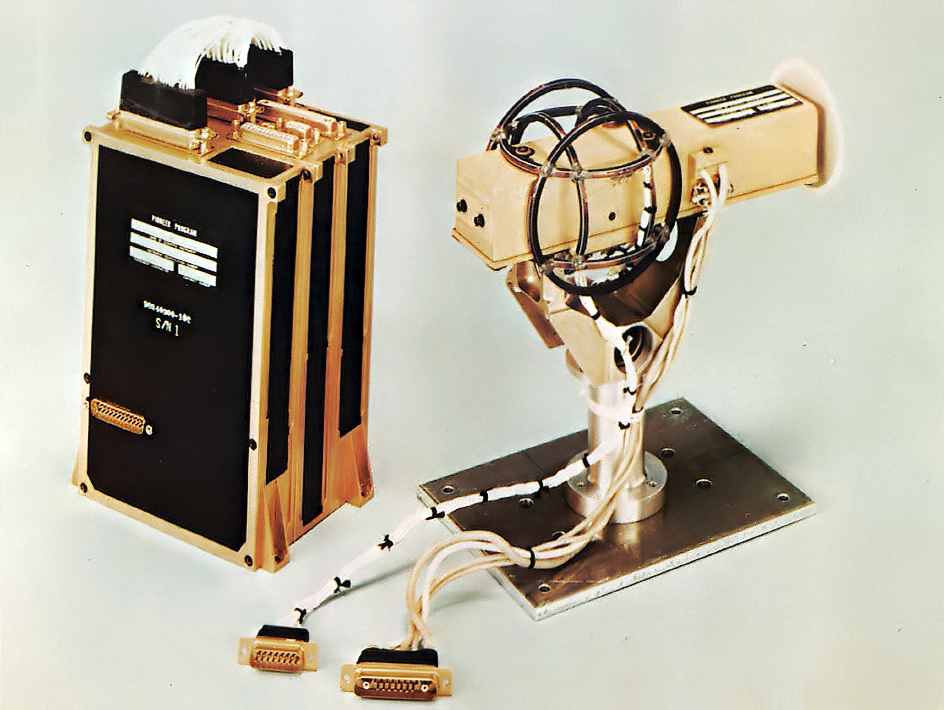

X-raying equipment in search of bugs

First, Deeley’s team X-rayed new, American-made equipment, including some 250 typewriters. NSA analysts disassembled, reassembled, and scanned every component. They installed anti-tamper tape and sensor tags on the inside and outside of each typewriter. When it came time to ship them to Moscow, armed guards escorted tamper-proof bags, known to be unavailable in Russia, through Fort Meade, Dover Air Force Base, Frankfurt, Germany, and then on to Moscow. Once in Moscow, the agents swapped all the existing bug-riddled equipment and brought it back to Fort Meade for examination.

After ten weeks of analyzing equipment brought back from Moscow, the team believed Project Gunman might be a bust until one of the embassy inspectors noticed a coil on the power switch of one of the typewriters. The coil was innocuous enough; all the new typewriters contained additional memory requiring more circuitry and coils. Curious, the agent X-rayed the machine. There, he could see that inside an unassuming metal bar that ran the length of the typewriter sat a tiny magnetometer.

Magnetometers measure slight distortions in the Earth’s magnetic field. The unassuming device converted the mechanical energy from each keystroke into a recorded disturbance for a small radio that transmitted the notes to Soviet agents, who could be parked outside or across the street. Soviet listening posts could turn the magnetometer on or off at will if they suspected bug sweeps.

This tiny recording device became the first of what we now call a “man in the middle attack.” Soviet spies were pilfering American messages, intelligence, and memos within seconds of their creation, before secretaries could even finish unspooling the paper. It was all virtually undetectable and instantaneous.

American officials never discovered how the Soviets got the implants on the machine coils in the first place. Leading theories included intercepted shipments, a mole, or building technicians who came into the building, ostensibly to investigate a failing elevator or electrical system.

Now, some 45 years later, this “man-in-the-middle” attack vector of choice works roughly the same through Zero Day bugs in platforms and software like Microsoft Windows, Word, iOS, as well as printers, webcams, and other hardware.

It’s these zero-day bugs that are putting individuals and businesses on a new digital front line of cyber war and espionage with very little support from the government.

Unlike the analog era where East and West technology different significantly, today’s computers, phones, and networking all operate more or less the same worldwide. Windows 11, iOS, macOS, Linux, and more are fundamentally the same in the U.S., Europe, China, South America, and even in black market phones in Russia. Meaning cyber attacks pose global risks. Like a human virus, no one is immune, and any weaponized attacks can “boomerang” back to a home country.

Security researchers and government officials know that the Russians and Chinese are in the U.S. water and power grid. They’re inside businesses just like the typewriter magnetometers were in the U.S. Embassy in the 80s. Because of the low barrier to entry in cyberwarfare, the Iranians, North Koreans, and possibly every other nation can get in without the expense of traditional missiles or navies.

But unlike traditional warfare where a country could expect its government to put up defense, U.S. government officials have largely left businesses to defend themselves. There simply is no way to guard against all online threats. In this read about, America’s addiction to Wi-Fi enabled devices from lightbulbs to thermostats poses a massive attack surface unseen anywhere else in the world.

Continue reading how Zero Day bugs impact businesses and organizations like yours