The move from analog to digital technology reveals new global risks for private businesses and individuals

Americans are the most connected and digitized economy in the world. Every smart lightbulb, laptop, phone, router, switch, car, Wi-Fi-enabled oven, and even dishwashers are an attack surface that can be exploited by Zero Day bugs.

Zero Days get their name because once you discover you have a problem or a bug, you have zero days to fix it before it’s a problem.

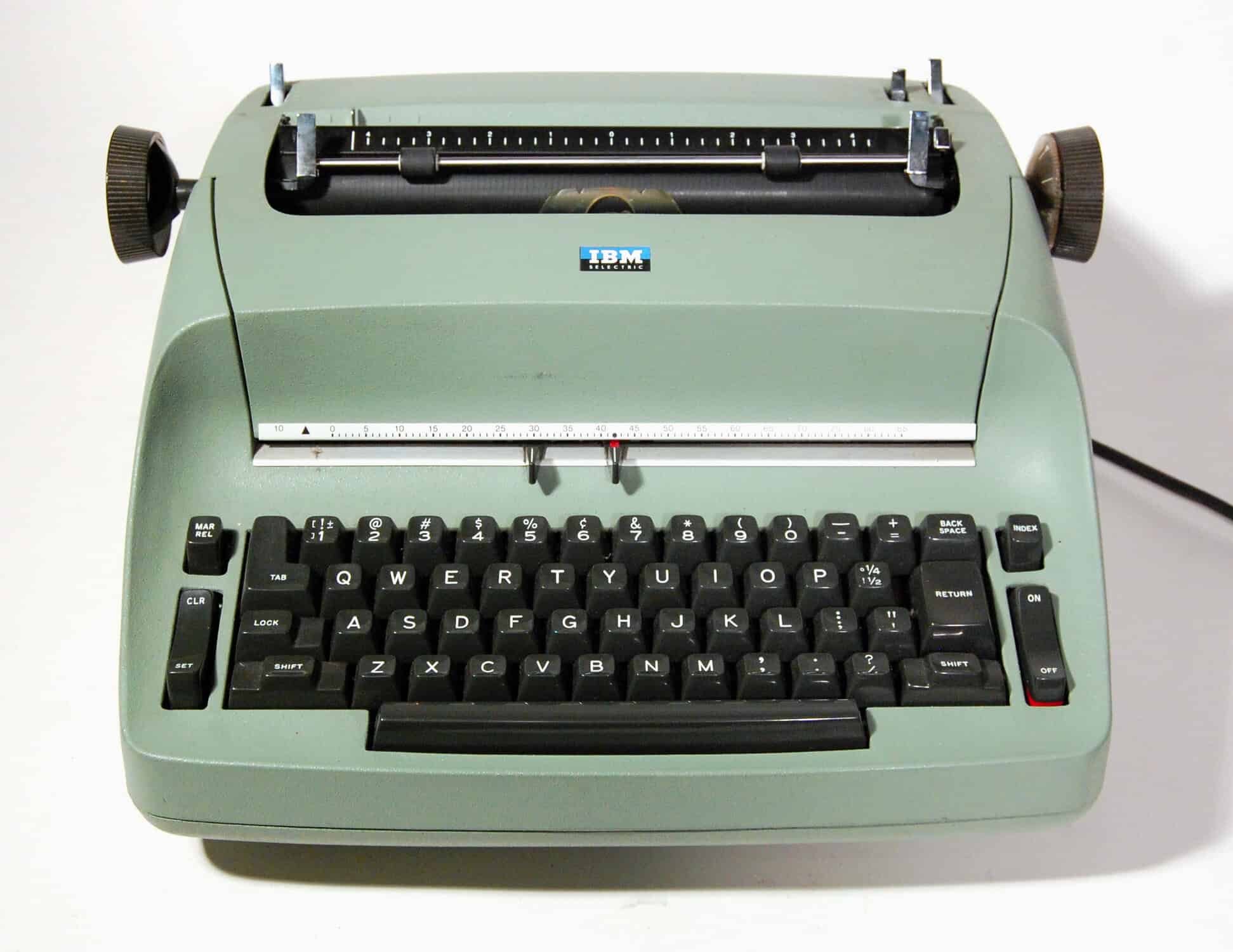

Zero Days are the modern equivalent of the Soviet magnetometer in a typewriter, but because they’re digital, they can spread into an entire network from just one weak, old, or unpatched device such as a Wi-Fi enabled air conditioner, phone, fridge, router, or printer.

There is a cottage industry of exploits and market forces for Zero Days. The cost of software bugs has ranged from as little as a few hundred dollars in the early 2000s to as much as $2-3 million dollars today.

Market forces have caused the costs to rise as Microsoft, Apple, Google, and others have made security a priority and dried up a lot of opportunities. But software bugs — the kind that enable an attacker to install malicious software and record your screen or keyboard or even take over your mouse — still exist. Some are likely known by hackers and governments, including in the U.S., who don’t disclose the bugs so they can spy on threats. Disclosing the bug would prompt software developers to patch them, closing the access.

How a Zero Day takes down the power grid

The Ukrainians went first. In December 2015, just before Christmas, workers at a local power plant watched in a cold sweat as their mouse cursors began moving across their screens, systematically shutting down the motors that generate power to over 230,000 Ukrainians.

Later attributed to a Russian group known as “Sandworm”, they used malware originally written by American NSA officials called BlackEnergy. The system exploited a Zero Day bug then known by governments but unknown to Microsoft in Windows. It allowed for a fully remote PC takeover. To add to the misery, the Russian hackers also disabled the Ukrainian backup systems, then shut off all the machines and computers entirely.

Two years later, another bug dubbed “NotPetya” (a play on a former bug named Petya, itself named by American officials after one of the two rogue Russian satellites in the 1995 James Bond film Goldeneye), began to wreak havoc on machines worldwide that disrupted shipping companies like FedEx, hospitals, and millions of machines. It, too, was a variant from code dubbed EternalBlue, originally written by American NSA agents.

How does an American-made exploit end up harming American companies like FedEx?

Software leaks and can be copied. Because everyone uses much of the same technology stack globally, these attacks can “boomerang” back on us, like a missile that can be remotely overtaken mid-air.

The threadline is the stakes are high, the costs are high, and the skill level required to run these attacks are high. American code has leaked or been pilfered by North Korean, Chinese, Russian, and Iranian hackers. Some are state-backed, some less so (like in Russia). And unlike missiles or submarines, the cost of entry to use these tools requires little more than a laptop and a good internet connection.

Unlike a typewriter in the Cold War, all the equipment in use today is roughly the same worldwide. The Russians have all the same Intel-powered computers as American schools and universities. The Chinese use the same Windows, Mac, Android, and iOS platforms and services as U.S., Canadian, and Mexican trucking companies. Many of the bugs are hard to track, unknown to most people, and take weeks to trace back. They’re also deceptively simple, often just erasing hard drives or encrypting files in ransomware attacks that most attackers have no intention, or even the ability, to give back even if the ransom is paid.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security has preparedness plans for all manner of natural disasters, hurricanes, floods, wildfires, tornadoes, heat waves, and multi-day power outages. Most of these plans are short-term, like how to deliver water after a hurricane. There is no plan for a large-scale cyberattack that could potentially deny millions of Americans power for weeks or months. There is no plan for how to retaliate against a state actor if large hospital networks or, indeed, entire local and state governments are locked out of their machines, voting systems, records, databases, and services.

And for good reason. Any retaliation against a state actor likely invites an escalation of attack. Presidents Obama, Trump, and Biden have wrestled with this and decided a tit-for-tat escalation is more harm than good to American interests. It’s mutually assured destruction for the cyber age, but with code and not nuclear weapons.

This means one thing for American businesses and individuals: you’re on your own in the event of an attack. Large employers or healthcare providers can and do receive assistance from the FBI, CISA, and other federal agencies. But none of them have any ability to “hit undo” or attack back. Their support is strictly guidance, with best practices, like how a doctor might tell you to rest and drink fluids to fend off a cold.

Infosec and IT security teams know the harsh reality that everyone is vulnerable. Every machine is as vulnerable to a cyberattack as human bodies are to a physical threat. There is no way to stop everything, and any effort to try would require decades, cost money, and necessitate updated hardware, software, and replacement components. Most people are not excited about spending a few hundred dollars on a new internet router.

This is where Vantage Point can help. We’re not infosec teams, nor do we sell coding or programming services. Instead, we help businesses create continuity of operations plans (COOPs) and test their internal processes against various situations and scenarios.

- Can your team function without email for a day? How about for a month? After email hosting provider Rackspace was attacked in 2023, everyone’s Microsoft Exchange email was completely inaccessible for more than six weeks.

- Would your company continue to fulfill orders if it was discovered your website was leaking credit card information?

- How would your PR and communications teams respond if your nursing home was found to be leaking patient records to an unknown source?

- How well can your team spot email phishing? Phishing remains the number one source for malware and ransomware implants. It’s easier and faster for outside agents to trick Jenny in Payroll or Alvin at the Reception Desk to click a malicious link than it is to find and deploy a Zero Day bug in macOS.

- Could your local county government continue to respond to 911 calls, inspect health code violations, treat water, order road salt, plow roads, and record tax payments if every computer in the county was attacked?

VPC can help design tabletop exercises and other live-action drills to help you prepare for this reality. Because it is a reality, as witnessed by Dallas, Tulsa, Jackson County, MO, Vermont Health Network, Minneapolis Public Schools, LASD, Ascension, Scripps Health, JBS Foods, MGM Resorts, Kaseya VSA, and millions more.

Request more information and get started

Start here to request more information for your team.

"*" indicates required fields